Ganbei!

The Blind Squirrel's Monday Morning Notes. Year 3; Week 11.

This week, the 🐿️’s Chinese ‘booze’ edition. Cheers!

Ganbei!

Trigger warning for my American readers: we start this week’s note discussing an item that may be becoming a touch more expensive for y’all.

The 🐿️ first moved in Hong Kong in the late 1990s at about the same time as an acquaintance (later to become a great friend) who had been sent out to Asia by London’s most distinguished wine merchant to build the firm’s fine wine business in China.

Winemakers around the world were still giddy from Premier Li Peng’s 1996 endorsement (to the National People’s Congress of all places!) of the health benefits of wine versus the popular local white spirit baiju. However, my friend had an overwhelming job on his hands. Wine import duties in Hong Kong were a massive 80% and there was no (grape) wine drinking culture in China yet to speak of.

My friend did, however, have a secret weapon up his sleeve. In order to help kick start the business, his chairman had carved out a healthy share of the company’s en primeur allocations of the Bordeaux Grands Crus in order to entice a new cohort of fine wine collectors in the region. The problem was that, apart from a few local hotels and restaurants, my friend did not yet have any clients.

To hold on to that generous allocation, he initially leaned heavily on the (very grateful!) European expat community in Hong Kong in order to make his early sales targets. Early clients were able to secure the sort of rare allocations normally only made available to the highest of high rollers on the merchant’s London client list.

A few years later, my friend and his competitors were glad to move on from young bankers and brokers. They had successfully lobbied the Hong Kong authorities to cancel all wine duties by 2008 and, fast forward to today, have managed to turn the city into one of the most vibrant trading hubs for fine wine in the world.

By 2013, China was consuming more red wine than the French and was even giving the great wines of Bordeaux and Burgundy their own local names.

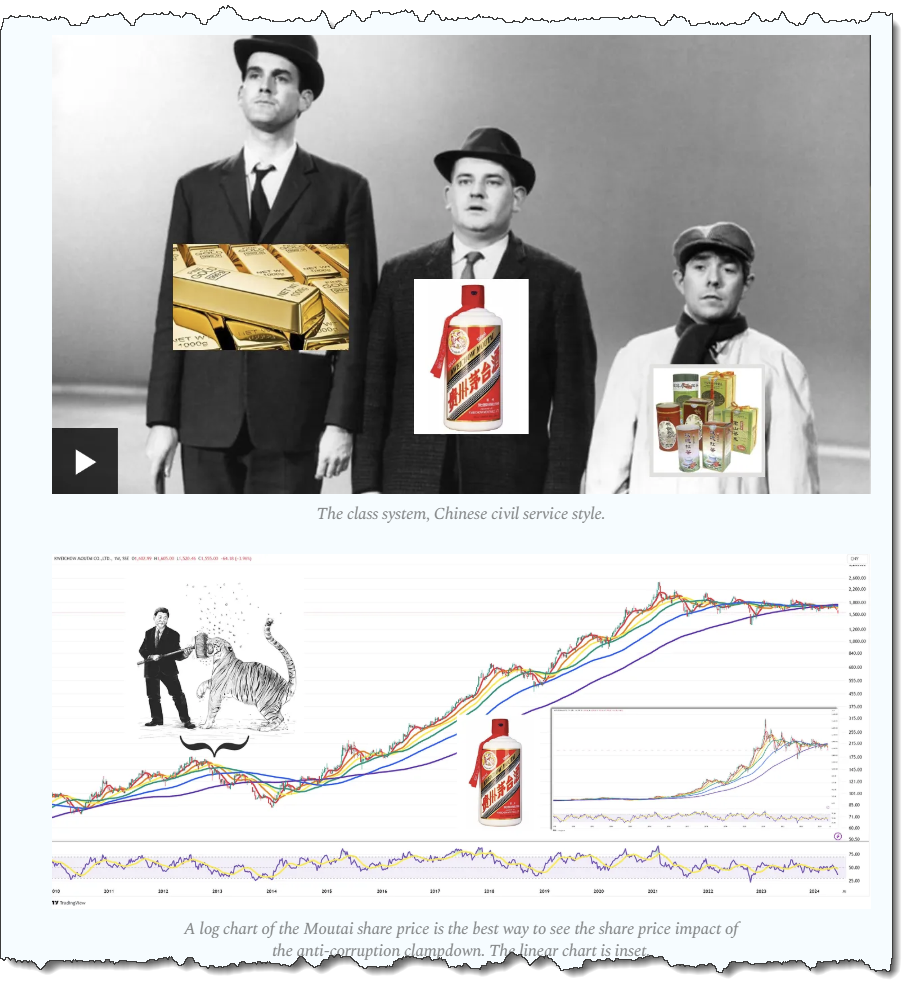

By the mid 2010s, fine wine had become an enormous business in China. Bottles (as well as their counterfeit versions) were playing an enormous role in the banqueting and gifting culture and taking significant market share from the local liquor giant, baiju.

The 🐿️ touched the role of baiju as a unit of value and exchange in China last year. We ran through how sales of fine wine, local spirits and even boxes of tea collapsed with Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive starting in 2012. Worth recapping if you missed it last year.

The last few years has seen a market share fightback by baiju versus foreign wines and spirits which are all attempting to localize their brand language for a Chinese consumer that, as discussed in ‘Hot for Hot Pot’, is embracing Guochao 国潮 (literally ‘nation trend’ or ‘China chic’) consumption habits.

In these heightened geopolitical times, Baiju could also be in hot demand in its traditional diplomatic role. As Henry Kissinger joked to Deng Xiaoping in 1974, “If we drink enough Moutai, we can solve anything”.

It is not uncommon for senior Chinese businessmen to take a younger ‘stunt double’ colleague with them to evening drinking sessions to respond to toasts on his boss’ behalf. Given that Trump is teetotal, we may have finally found a diplomatic use for Marco Rubio (although he may have to raise his game from bottled water).

But it is not all plain sailing from here for the national spirit. Baiju has some generational challenges to contend with. Many younger Chinese consumers need encouragement to embrace their fathers and grandfathers’ favorite fire water, preferring beer (more on that later), designer coffee or bubble teas.

For those wanting to get fully up to speed on the baiju sector, learn its politics and how to differentiate your Jiangxiang (sauce aroma) from your Qingxiang (light aroma) varietals, I strongly recommend that you check out 2 excellent notes from Moatless Capital on Kweichow Moutai (sauce) and Shanxi Xinghuacun Fenjiu (light). Those of you short of time should scan his 2021 tweet thread on Moutai at a minimum.

We will go through the baiju industry structure and some numbers as well as how the 🐿️ is playing the China ‘booze’ space in more detail below.

I want first to turn to the less alcoholic grain-based alcohol - beer. Archeologists have found evidence of brewing activity in China that dates back over 9 thousand years. We do know for sure that beer’s popularity was eclipsed by rice wines (huangjiu) and other spirits at some point during the latter part of the reign of the Han dynasty (206BC to 220AD).

Modern brewing in China dates back to the colonial occupations of the early 20th Century. Today’s mainland breweries owe part of their heritage to a mixture of German, Czech, Polish, British and Japanese occupiers. Tsingtao, arguably China’s most recognizable beer brand, is a quintessential geopolitics and history lesson in a bottle (or can but much better from a bottle - IYKYK).

The brewery was established in 1903 by the Anglo-German Brewery Co. Ltd., primarily catering to German settlers in Qingdao, then a German colony. The brewery was initially named Germania Brauerei and was set up to produce pilsner-style beers, adhering to the traditional German Reinheitsgebot (Purity Law), which stipulated that only water, barley, and hops could be used in brewing.

During World War I, Japan besieged and then occupied Qingdao and took control of the brewery. The Dai-Nippon Brewery, which later became part of Asahi Breweries, acquired the business and introduced rice as an ingredient to the brew. After Japan's defeat in World War II, the brewery changed hands several times before being nationalized in 1949. It then became the first mainland Chinese company to IPO in Hong Kong in 1993 (168.HK).

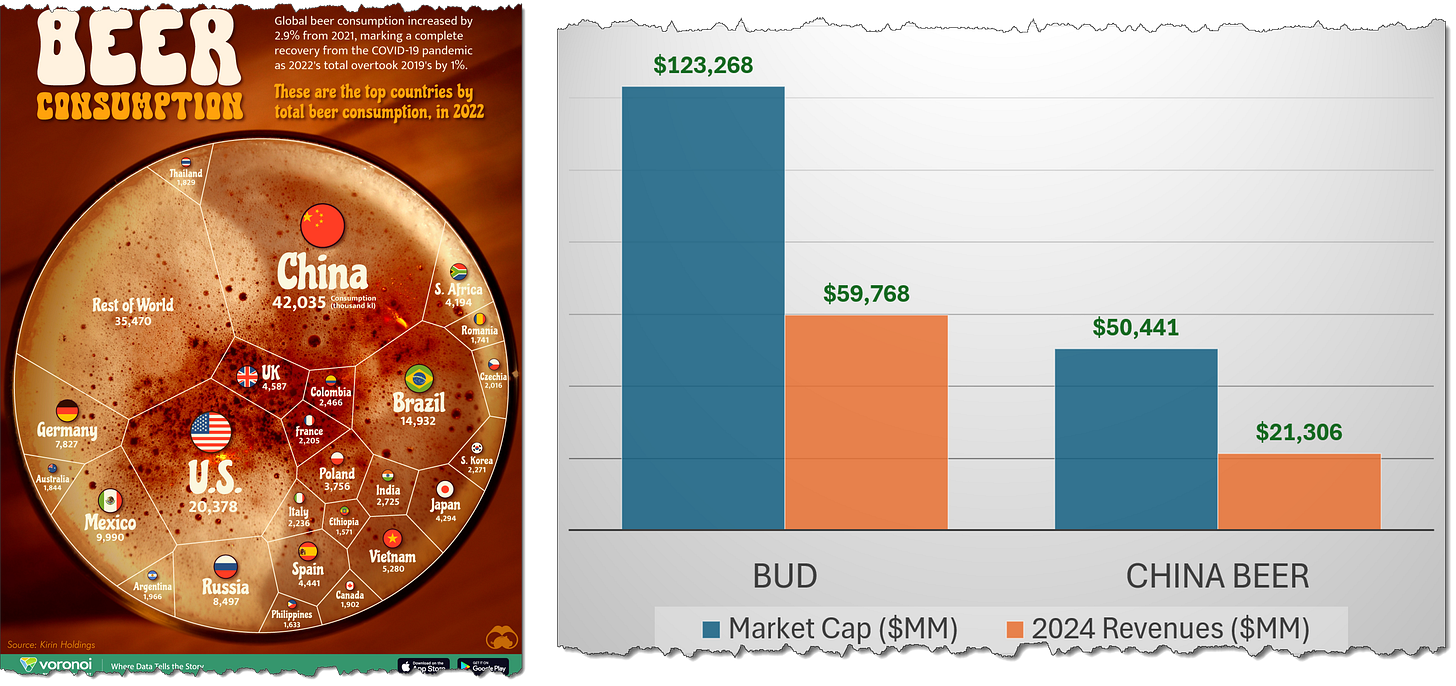

China's beer industry is now the world's largest by volume consumption. With demographic and taste shifts, the industry faces similar challenges to the baiju players. It will struggle to grow at a faster rate than the broader economy and must instead focus on premiumization and capital allocation.

However, the listed market cap of China’s breweries is currently tiny relative to its position in global beer consumption. Currently the sector amounts to only 41% of the market cap of Anheuser-Busch InBev BUD 0.00%↑ alone, and 31% of that total Chinese beer market cap is represented by Budweiser Brewing APAC (1876.HK) which itself is 87% owned by the ‘King of Beers’!

The China beer industry is expected to grow cashflows at an almost double digit CAGR over the next 3 years (2.3% more than InBev over the same forecast period). This number could well be a lowball if brand premiumization strategies are successful. Furthermore, the industry has almost $8.5 billion of net cash on its collective balance sheet. There is plenty of scope of capital allocation tailwinds via buybacks and increased dividend payouts.

However, China’s beer market is dwarfed by the $479bn of listed baiju market cap. Baiju revenues are growing at a faster clip, with sustained EBITDA margins of between 50% and 70% for the leading players.

Baiju market share is dominated by half a dozen regional champions, led of course by Guizhou’s Moutai and its instantly recognizable US$300 red and white bottles of the legendary ‘Flying Fairy’ (Feitian Moutai or 飞天茅台).

Like its brewing cousins, the listed baiju players have robust balance sheets with aggregate net cash positions of over $55 billion! The average dividend yield for the sector is indicated at 3.3% (roughly in line with the average for Chinese equities).

Recent corporate governance initiatives are encouraging listed companies to refocus on their capital allocation strategies. Goldman Sachs estimates that Chinese dividend payouts could increase by 40% in 2025.

The cash rich beverage companies are yet to start any significant share repurchase activity but are leading candidates (and market leader Kweichow Moutai has started to make buyback noises). I expect this to be a key theme of earnings season in April.

So 🐿️, do you fancy a chilled Tsingtao or a crisp shot of Guilin Sanhua?

Come and join the beer and baiju party in Section Two!