Drones: Crashin' or Cash in?

The Blind Squirrel's Monday Morning Notes. Year 3; Week 12.

This week, the 🐿️ contemplates whether an inability to fly them is a reason not to trade drones (and other unmanned flying objects).

Drones: Crashin’ or Cash in?

Confession. As a keen photographer, I have always thought drones were pretty cool but have sadly crashed and broken every single one that I have ever bought within 24 hours of unsealing the packaging. As such, the following lines from a 2015 Wall Street Journal gadget shopping guide had this rodent’s full attention:

“Everybody loves the aerial look of drone photography, but let’s face it—not everybody was born to be a drone pilot. We’ll soon think of drones more like cameras than helicopters, as their technology evolves to compensate for novice mistakes and foolhardy fliers. One maker, Lily, plans to release a waterproof model that launches when flung into the air, then follows you around as you kayak, ski or take a sunset selfie on the beach.”

The 🐿️ instantly became one of the ‘over 60,000’ excited ‘early adopters’ who sent $500 deposits to Lily Robotics to secure an idiot-proof ‘follow me’ camera drone after watching this promotional video 👇.

Sadly, I never got my semi-autonomous drone (or indeed my refund!). On the positive side, my social media timelines were spared from some truly obnoxious powder skiing ‘Poast videos’.

I should have paid attention to some of the skeptical questions that lurked in the YouTube comments section at that time. Without anti-collision capabilities, Lily would have almost certainly wrapped itself around an Alpine conifer on its first outing in the Chamonix valley!

We now know that modern drones are manufactured with sufficiently sophisticated obstacle avoidance sensors and software to allow the Israeli Army to operate them in the underground tunnel networks of Gaza City.

Up until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for most people, military drones were those multi-million-dollar unmanned war jets from Northrop Grumman and General Atomics that waged remote warfare in deserts of the Middle East or hunted down Jason Bourne in the Yukon wilderness.

The role played by drones in the war in Ukraine changed that common perception almost overnight.

Last November when introducing ‘EuroMIC’, our basket of European defense stocks, the 🐿️ observed that low-cost drone technology was forcing a major rethink by military strategists and planners historically mainly focused on budget busting fighter jet, battle tank or warship programs.

Inclusion of the likes of Safran, Thales, Dassault Aviation and BAE Systems gives the 🐿️’s ‘EuroMIC’ basket plenty of exposure to the military drone and UAV markets, but I was curious to take a closer look at more direct opportunities in the military (and civilian) drone markets. I suspect that it is a small market that could receive disproportionate spending attention.

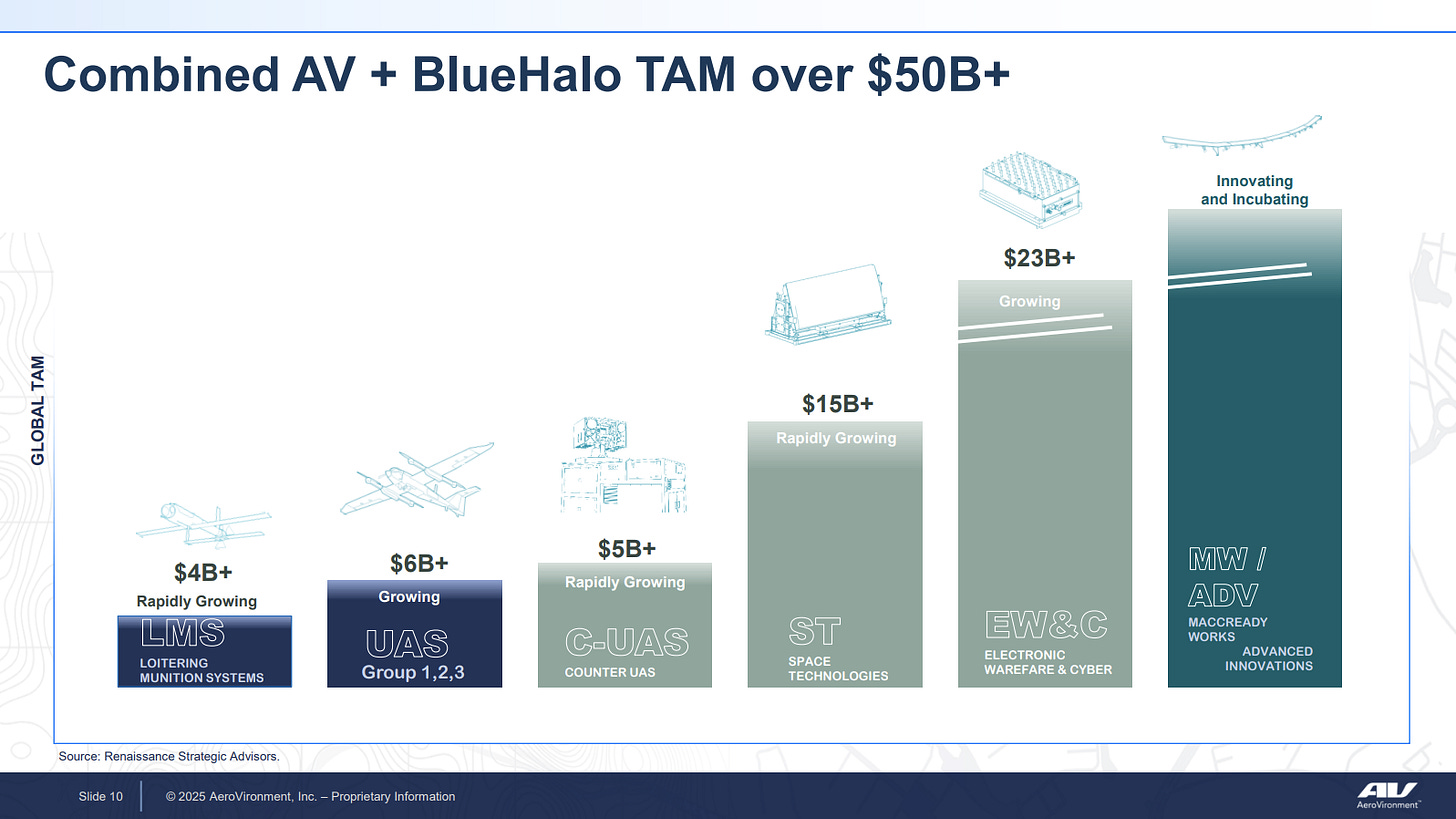

The numbers are compelling. The global military drone market, valued at $21.8bn in 2024, is projected to triple to $57bn by 2033. Given what we have learned about drone and UAV combat effectiveness in the past 3 years, that number feels low to this rodent.

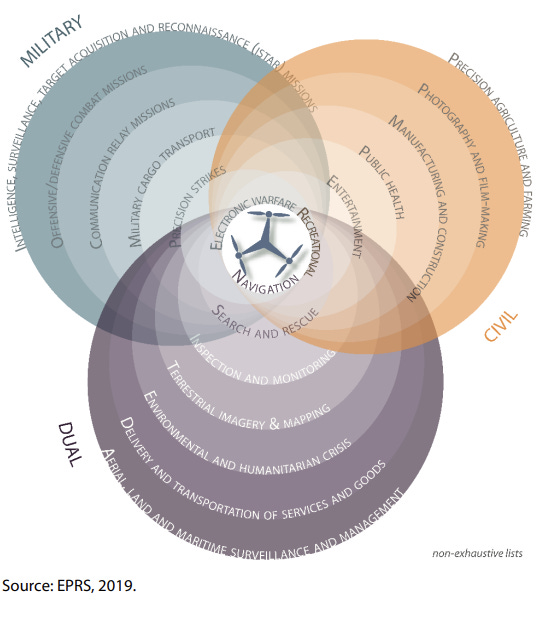

And then, the market opportunity for drone countermeasures is vast and growing equally rapidly. The drone industry is also adjacent to space and satellite technology, electronic warfare and cybersecurity markets.

Meanwhile, the commercial drone market, which was sized at $5.5bn in 2023, is expected to also triple to $18bn over the same period (again a lowball in my view as civilian (dual) use cases with expand with the additional defense spend). UAV (and associated software) systems are now an integral part of multiple civilian industry verticals:

Energy Sector: Pipeline and electricity grid inspection and monitoring.

Agriculture: Precision agriculture, including crop monitoring, spraying, and analysis.

Infrastructure: Inspection and maintenance of civilian infrastructure (roads, bridges and railways).

Public Safety and Security: Expanding adoption for surveillance, emergency response, and critical infrastructure protection.

Just as the importance of drones to defense and multiple civilian applications emerged, once again the world woke up to the fact that, barring some isolated areas of expertise in Turkey and Iran (and now of course Ukraine), the global drone supply chain was dominated by China (see also batteries, electric motors, nuclear power plants and rare (not raw!) earths).

FPV (First-Person View) drones have transformed from hobbyist tools to essential tactical equipment in modern military conflicts. What were initially just used for racing by nerds and promotional sales videos for real estate agents, are now serving critical roles in reconnaissance, target identification and direct strikes.

The majority of FPV drones and drone components are manufactured by a small number of suppliers, primarily located in China. DJI, the major Shenzhen-based player, held a staggering 70% global share of the FPV drone market until recently.

Realization of this Chinese supply chain dominance triggered the creation (in 2020) of the Blue UAS program by the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit to vet commercial drones for military use and make it easier for the military to buy ‘off-the-shelf’ technology.

The recent unilateral decision by DJI to switch off the geofencing safety feature that made their drones unable to fly in sensitive US geographies has triggered drastic action to further accelerate drone procurement. They are even tapping Ukraine, the military “drone capital of the planet”, for assistance. Let’s hope The DoD does not get any ‘toned down’ versions.

This new sense of urgency has created a significant opportunity for smaller private sector players in the UAS market. These players tend to be more agile, niche-focused innovators, often leveraging existing commercial technologies as well as satisfying new ‘friend shored’ procurement requirements.

The USMIC may continue to milk its multi-billion-dollar Reaper, Sentinel, Global Hawk and Predator programs but the urgent demand would appear to be at the retail-priced end of the drone market. This has created a target rich environment for a number of (politically connected) small caps and Silicon Valley start-ups.