Deal Drought

The Blind Squirrel's Monday Morning Notes. Year 3; Week 16.

Wasn’t it supposed to be a ‘Golden Age’ for dealmaking and investment banking? Asking for a friend.

Deal Drought

If I am honest, these markets are probably triggering PTSD for many recovering investment bankers. The 🐿️ has certainly seen the movie before. Walking onto the Goldman Sachs trading floor in Hong Kong on the morning of June 24th, 2016, just as exit polling and early counts were clearly showing that Britain had voted to leave the European Union, I knew what the weeks ahead would probably entail.

When equity implied volatility (VIX) doubles in a session and the MOVE index of US Treasury volatility spikes into a distress zone (yes, 80 was a very high level in those days!), one thing becomes immediately clear to anyone in the capital markets or advisory businesses. Deals are on hold until further notice.

The episodic businesses of Initial Public Offerings and public mergers and acquisitions require calm markets and confident CEOs. Investment bankers cannot do anything about a choppy tape or a cloudy economic outlook, but they are in the business of selling confidence (no, not in that way!).

Back to that early summer morning of 2016. My visit to the trading floor to chat with senior traders and salespeople was not because I had nothing better to do on the deal front that morning but rather because I knew just what was coming next. I was gathering nuggets, views and anecdotes in anticipation of the inevitable “at times like this it is essential that you all get out in front of your clients” call from leadership in New York.

The ‘macro shock 101’ playbook for bankers was pretty predictable. By early afternoon, the invitations had been emailed out to all clients in the region to join an exclusive “Update on Global Markets” conference call that evening during which strategists and bankers would share compelling charts and data in an attempt to build confidence with clients (and demoralized colleagues) that normal business would quickly be resumed. Kind of like a CNBC “Markets in Turmoil” special, but without the red flashing chyron or Bill Ackman in tears.

The call would be repeated several times over the ensuing weeks. The list of attendees would atrophy over time until the point at which the list of attendees was made up entirely of colleagues plus a couple of bored junior private equity associates. Meanwhile, senior bankers’ days were filled with the guess work of recasting budget estimates and deal pipelines.

Pretty soon, the “revised travel policy” memo hits inboxes inspiring the snarky question as to how essential “getting in front of clients” must indeed be if nobody is allowed to get on a plane. The water cooler chatter is punctuated with gallows humor about bonus pools becoming bonus puddles. Then, just like clockwork, comes the request from senior management for initial ‘RIF’ lists. Those days are not missed by this rodent.

‘Deal World’ frankly had it coming

A spell in the penalty box was probably earned by deal world. Let’s take a trip down memory lane to the quasi-comedic frenzy of 2020-2021:

Square (now Block)’s $29bn acquisition of BNPL disruptor Afterpay is still celebrated in the champagne bars of Sydney’s Circular Quay while the market cap for (the whole of!) Block Inc. XYZ 0.00%↑ is now barely above $33bn;

The IPO of Rivian. RIVN 0.00%↑, with estimated 2021 revenues of $55 million, raised $12bn at a valuation of $66.5bn (and was ‘worth’ $100bn after first day of trading). The EV maker’s $5bn of 2024 sales are now valued by the market at $13bn;

Any SPAC merger priced ‘in the arena’ by Chamath Palihapitiya. Honestly, take your pick! Choices include Opendoor OPEN 0.00%↑ (-89% from pricing), Clover Health CLOV 0.00%↑ (-83%) and ‘the relative champ’ fintech SoFI SOFI 0.00%↑ (-61%).

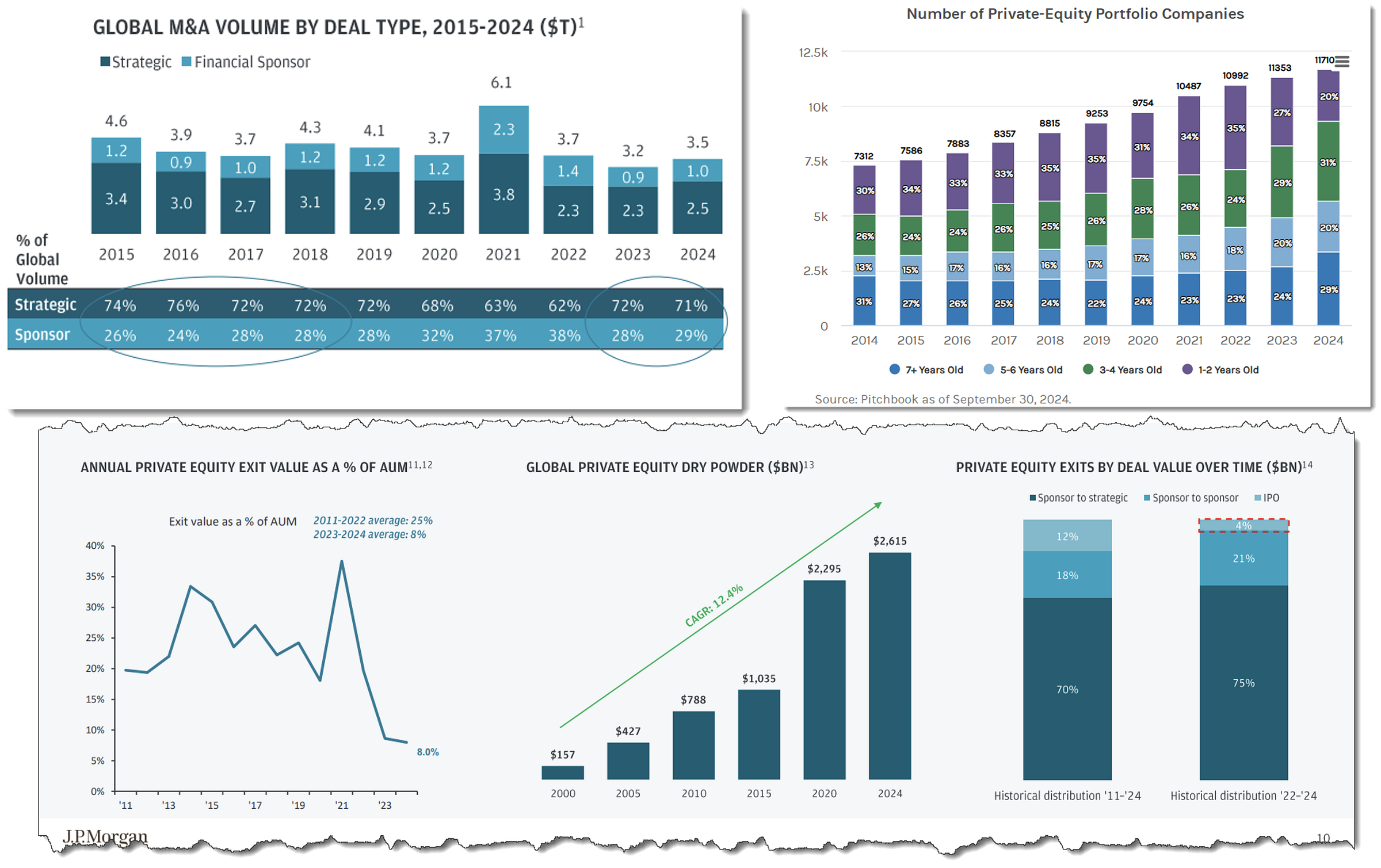

The end of the free money era starting in June 2022 came at deal world hard, as aggressive monetary tightening dramatically altered the deal making landscape. The IPO market entered a nuclear winter, and M&A volumes collapsed by almost 40%.

A much-anticipated rebound in deal activity did not materialize as hoped in 2023 and 2024 only saw a modest pickup in total deal volume as the total global deal count continued to drift lower.

C-suite concerns about that ‘recession that never came’ probably account for much of the drop off in deal activity. Regulation and strict anti-trust enforcement certainly played a part and was certainly vocally criticized by the Silicon Valley overlords for jamming up that cozy conveyor belt running between the VC portfolios and the cash rich giants of mega-cap tech.

The real problem was Team Saddlebags

However, the real driver of the deal downturn was our old friend ‘Team Saddlebags’. When this rodent first started in the industry, the world of private equity occupied a niche corner of the financial landscape. Junior bankers had all of course read ‘Barbarians at the Gate’ but in no way were KKR (or Blackstone or Carlyle) anywhere near the top of the potential acquirer list prepared for every ‘sell side’ M&A assignment.

Fast forward less than 2 decades and the giant financial sponsors dominated the revenue wallets of the investment banks. Investment banking coverage had to be rearranged as a result. What was the point of a generalist financial sponsor coverage team (aka the ‘concierge department’ IYKYK 😉) when private equity related transactions accounted for half of the business of most industry sector teams?

The burgeoning private equity groups were evolving into mirror images of the investment banks that covered them. PE software investors wanted to be covered by software bankers. Most of the ‘concierges’ found themselves restyled as leveraged finance capital markets originators, i.e., keepers of the keys to their parent bank’s balance sheet which was the resource that Team Saddlebags really wanted.

In a final irony, with the recent growth of the direct lending arms of ‘Big Privates’, sponsors are now looking to disintermediate the banks in the business of sourcing the leverage for their deals. As far as the 🐿️ is concerned, it is this excess leverage that is the chief contributor to the stasis in deal markets.

It turns out that Big PE was so successful at persuading asset allocators that they could all be the next David F. Swensen, that they created excess competition in the business of harvesting risk premia from private markets. In an era of ultra-low interest rates, high leverage and financial engineering could compensate for the higher prices paid.

However, today, the LBO models simply refuse to spit out the internal rates of return that were promised to LP investors when 10-year yields are above 4% - whatever creative adjustments are made to modelled forward cashflows (the mythical ‘Adjusted EBITDA’). As such, the ‘dry powder’ has accumulated while portfolio exits, which require funds to engage with a moment of truth on the valuation front, have fallen off a cliff.

The 🐿️ will refrain from returning in detail to the topic of the mark-to-market practices of the private asset world (see prior rants). It is far too easy to blame the lack of recent IPOs on ‘volatility’ or ‘unfavorable market conditions’. And no, it is not a function of a failure of active public markets investors to ‘understand’ or ‘believe in’ some kind of new ‘valuation paradigm’.

The truth is that the increasing quantity of ‘aged inventory’ in PE portfolios has been the absence of willing sellers of assets at the prices implied by the multiples of comparable companies already listed on the market.

Strategic purchases by listed corporates are similarly challenged. For listed companies to pay prices for assets where they are currently marked within PE funds will guarantee a messy encounter with the Wall Street analysts’ M&A EPS accretion/ dilution models. That’s not going to happen either.

The increased share of sponsor-to-sponsor activity in M&A markets (I’ll buy yours if you buy mine?) and the aggressive use of ‘continuation funds’ (can we just call them ‘side pockets’ like the hedge funds do and be done with it?) can only partially mask this growing problem.

It strikes me that the world of private assets needs the ‘air cover’ of a proper financial crisis so that all the GPs can link arms and - Thelma and Louise style - collectively re-mark all of their assets at levels somewhere closer to reality.

Until this type of reset actually happens, unfortunately Team Saddlebags is not of much use to Wall Street’s M&A and capital markets bankers as its most important customer.

In Section 2 below, we review how the optimism surrounding the ‘Art of the Deal’ re-entering The White House may have turned out to be a false dawn for my former colleagues and peers. There is an interesting way to play it.